Why Do People Love Stories? It’s All About Sex, Drugs and Rock ‘n Roll [Webinar]

There’s a scientific reason why stories can convince people to do things they thought they’d never do, like vote for Trump or buy a hybrid car.

And believe it or not, it all has to do with sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll.

But before I get ahead of myself, here’s a little background. I fell in love with marketing when I was a kid. I grew up in the ’80s. Nike had launched their “Just Do It” campaign; Apple was challenging IBM with their 1984 commercial; and Angela Bower had just hired Tony Micelli to help her while she got her ad agency off the ground on the sitcom, Who’s the Boss. While other kids wanted to be astronauts, doctors or lawyers, I wanted Angela Bowers’ job — I wanted to be a marketer.

A lot has changed in marketing since Who’s the Boss‘ heyday. Back then, advertising wasn’t about chasing clicks or breaching privacy. It was about telling stories, be it through commercials or billboards. And while audiences today are still watching shows, reading articles and lining up in droves to see the latest movie, ads themselves don’t seem to be working like they used to.

Why are we skipping commercials, but still watching the shows? Why are we blocking banner ads, but not articles? And why do we throw mall flyers in the trash, but pay $20 to go to the theatre to watch what is essentially a two-hour animated LEGO catalogue?

Stories engage our entire brain, which is why we remember them.

While half of our team members at Pressboard are content experts, the other half are software engineers and data scientists. This means that when we come up with a question, we turn to data to solve it. It also means that we’re constantly investigating the scientific reasons why human beings are still so in love with stories, but increasingly turned off by ads — and the results are a lot sexier than you’d expect.

Sex and Drugs

Think about your favourite movie for a moment. Have you ever wondered why you care about the hero of that movie so much? Why do we care if Private Ryan is saved, what happens to Forrest Gump or even whether the Barton Bella’s win the national a cappella championships?

We care because our brains are wired to do so; in fact, it’s entirely out of our conscious control. When you read a dry, fact-based textbook or come across an advertisement, the only areas of your brain that are engaged are the language processing centers. However, when you hear a story, many other areas light up, too. When you hear the gunshots in Saving Private Ryan, your sensory cortex is engaged. When Forrest Gump starts to run, your motor cortex is activated. Even when I told you the story about my childhood marketing influences, your hippocampus brought up your own memories so that you could compare them against mine.

Stories engage our entire brain, which is why we remember them and yet forget 99.99% of all the banner ads we’ve ever seen.

When we hear an emotional story, something even more powerful happens. Our brains release a hormone called oxytocin — and oxytocin is a hell of a drug. This hormone is released in the brain in just a few other situations: during childbirth, milk letdown, and sex. It’s the love hormone that helps humans recognize, trust and bond with one another. That’s why you fall in love with the hero of the story. When you hear a story that resonates with you on an emotional level, your brain releases oxytocin and you become more open to the characters. It’s even been shown that stories can influence your actions, inspiring you to make choices and change your behaviour in ways that reflect the story you’ve just heard. This same phenomenon is why we become so engaged in political campaigns. If political movements were a movie, the leader of your chosen party becomes the hero, and the opposing leader is therefore the villain. We vote based on emotional factors, including our affinity for the leader and their own personal story. If we relied purely on rational facts and data we wouldn’t have the need for drawn-out political campaigns, rallies. Campaign ads and mudslinging would be unnecessary, we could all simply read through a document that summarized the position of each party on each issue. In reality, we need the story in order to care enough to vote.

I know what you’re thinking: we’re not making movies or starting political movements here, we’re marketers and we’re just trying to open bank accounts or sell cars. But this raises an important question: does our brain react to a story the same way when a brand is involved?

Putting Theory to the Test

To answer this question, we again turn to science to put the theory to the test. Recently, Toyota had created and placed a few Prius branded videos using Pressboard with the objective of raising awareness of the car’s incredible fuel economy. The brand found that no one really cared when they included miles or gallon stats in their ads, so they wanted to try a storytelling approach. For one of their branded videos, they decided to recruit a real life couple and challenge them to drive a Prius until it ran out of gas. The video would be focused on the couple, with the Prius playing a supporting role.

At the beginning of the video, we meet the couple and they’re obviously quite in love, giggling and excited to take on the challenge together. As the challenge drags on longer and longer, however, you can see the relationship breaking down.

Anyone who’s been on a long road trip knows that spending several hours in a car with someone else can be a test. When the challenge hits about the seven hour mark, the girlfriend threatens to break up with the boyfriend if he doesn’t pull over. Finally, 12 hours in and at their wits’ end, the boyfriend parks the car and they surrender the challenge. The camera pans to the fuel gauge and we see that the Prius has only burned through an eighth of a tank of gas.

This video was by far the most shared video of the campaign, and the time spent was through the roof. We knew the video was popular, but we didn’t know why. I mean, we couldn’t read the viewers mind, could we?

Turns out we can. An EEG brainscanner (like the one in the image above) measures brain frequencies. Certain brain frequencies can tell us whether or not the viewer is paying attention. Others will indicate if the viewer is making an emotional connection to the message and if they’re encoding it to memory. We worked with Brainsights to measure the brain activity of over 100 people as they watched the Toyota video, and the results were incredible.

I mean, we couldn’t read the viewers mind, could we? Turns out we can.

Not only were there spikes in brain activity when the couple was introduced and as their relationship ran into conflicts, but also when the camera panned to the Toyota fuel gauge. Whenever the audience saw how much fuel had been used, those moments were encoded directly into their memories. In fact, the brainwave activity in the Toyota branded video was comparable to the frequencies seen when the same audience was exposed to NFL highlights and TV shows like This is Us.

Rock ‘n Roll

While Toyota wasn’t the hero of the story, they played an important supporting role. By incorporating their marketing objective into the story, they made it memorable in a way that a fuel economy stat never could.

So now the question is: when’s the right time to bring your brand into your content?

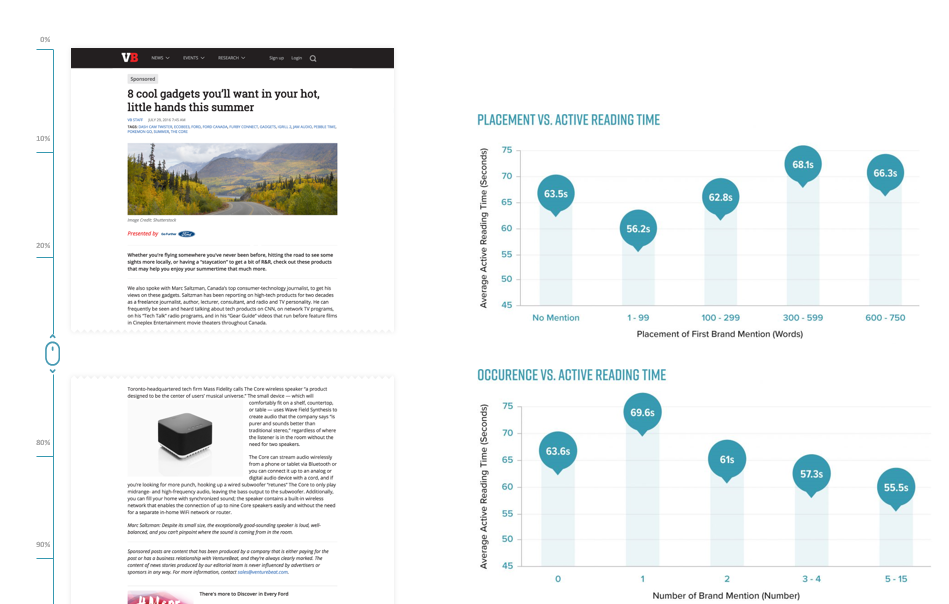

To figure out the answer, we studied over 300 brand stories (in article format) from all industries across dozens of different publications. Each of these stories were tracked by our software on a number of measurement criteria, including how active people were while reading them and how far they scrolled through the story.

To determine what makes a brand mention successful, we also looked at how early and how often the brand was mentioned in each article. We discovered that if the brand was brought up too early (before the story premise had been developed), the reader became less engaged. If the brand was brought up later on as a supporting character in the story, the engagement levels were even higher than in articles where the brand wasn’t mentioned at all. In these instances, the brand actually added to the story instead of taking away from it.

Which leads us to rock ‘n roll. In every band, the musicians play different roles. There’s the charismatic lead singer, the brooding bass guitarist and the eccentric drummer. It’s the combination of these musicians and instruments that give a band it’s synergy, which in turn creates beautiful, cohesive music.

Your brand doesn’t need to be the Mick Jagger of the story — but it can be a helluva Keith Richards.

The science of storytelling tells us that stories change our behaviour. The truth is, our brains are wired for them. Stories engage parts of our brain and release hormones that ads never will. Brands can play an important part in these stories, especially when they play a strong supporting role.

So next time someone asks you what your job is, let them know you tell stories — and that it’s basically just a lot of sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll.

The growing problem of fraudulent web traffic

Do you know if your readers are humans or robots? With nearly 1/3 of all web traffic..

Get your Content Marketing Fix

Sign up to receive tips on storytelling and much more.

We promise to respect your inbox.